Indonesia's role in one of the world's first pharmaceutical supply chains

Before WWII, Java produced most of the world's supply of an antimalarial tree bark.

Supply chain security is a key geopolitical consideration. Governments are taking a closer look at how critical goods are exposed to geopolitical manipulation. Indonesia is poised to play an emerging role in supply chain security with its natural resources, economic growth, and strategic position in the Indo-Pacific region.

Indeed, before World War II it was a critical producer of an antimalarial tree bark needed to manufacture quinine.

But first, a special welcome to my news subscribers and a thank you to my loyal readers for their support. If you like this post, please share it and encourage others to subscribe!

The source of quinine: cinchona bark

Indigenous South Americans have long used the bark of the cinchona tree to treat malaria and in the 1600s Jesuit missionaries introduced it to the rest of the world. Envied for its medicinal value, British explorers smuggled seeds and plants out of South America and grew them in similar tropical climates in India and Sri Lanka. Access to the bark, and thus, to antimalarial quinine became a strategic necessity for empires seeking to expand in the tropics. Without quinine, their personnel would be ravaged by malaria.

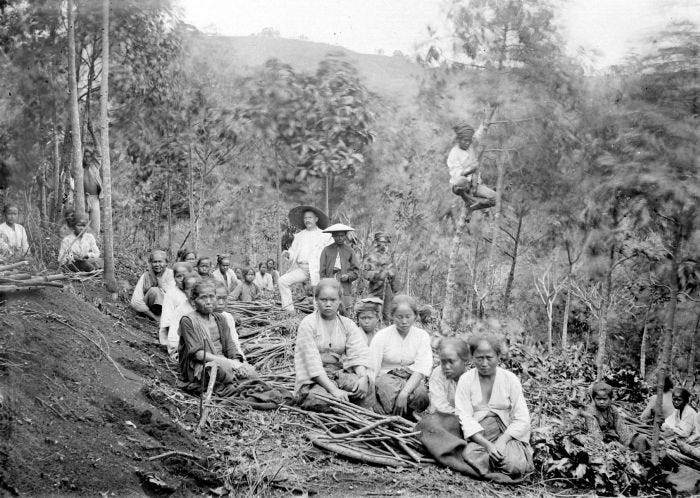

In the late 1880s, the Dutch colonial cinchona producers in what is now Indonesia had large plantations on Java and began to take over global production. However, the Java-based planters struggled with low prices and the German-controlled downstream industry. Geopolitics would change their fortunes.

Shifting geopolitics

Germany’s isolation after World War I and low prices for the bark prompted Dutch colonial authorities in Indonesia to step in. Taking advantage of the geopolitical shifts after the war, the Dutch became the architects of a global quinine supply chain. They established an agreement in 1913 which fixed a price for cinchona bark. The world’s first pharmaceutical cartel was formed, bringing Dutch colonial officials, planters, producers, and scientists together to dominate the global industry. Almost twenty years after the agreement, Java was producing 95 percent of the world’s cinchona bark.

The Allies lose their supply

Then World War II broke out, and no one was prepared for what was to come. The Japanese capture of the Dutch East Indies in 1942 cut the Allies off from the strategic resource. To make matters worse, the quinine reserves in Amsterdam had been captured by the Nazis in 1940 (Germany was also ahead in the research on synthetic antimalarials). Quinine shortages plagued the Allied war effort in the Pacific. The Allies had to develop their own supply of cinchona bark and were forced to manage malaria using other methods. The US began to establish cinchona plantations in Central America.

A scientific breakthrough?

In 1944, two eccentric chemists at Harvard University made a controversial claim that they had achieved the artificial synthesis of quinine. This would have eliminated the need to grow cinchona, and replaced the bark with a chemical process that could be replicated at an industrial scale. In fact, the scientists had only produced a precursor of synthetic quinine. The media no less hooked into the story and quickly perpetuated a myth that their process could be scaled up to solve the quinine shortage. The war ended the following year and synthetic antimalarials were developed within a few years after, and the cinchona plantations were needed no more.

Anatomy of a supply chain crisis

The story of quinine, with Indonesia at the centre, follows a pattern in many other supply chain security stories: a resource taken for granted, a single producer begins to monopolise it, geopolitics reveals risks, and science and policy struggle to develop alternatives. This pattern will be repeated again in our new era of geopolitics.

A special shout out in this edition to my designer, Harry W. Andrews, a Jakarta-based art director and graphic designer. He has a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Hawaii and a Liberal Arts Degree from Hilo Community College. He has over 20 years of experience working for professional firms and as an independent consultant. Harry’s clients have included Cardno, Ndevr, World Bank, and UNICEF. If you are looking for a designer, he comes highly recommended.